Code officials, design experts, developers and activists are grappling with a new challenge in the effort to decarbonize buildings: how to address embodied carbon in building and energy codes.

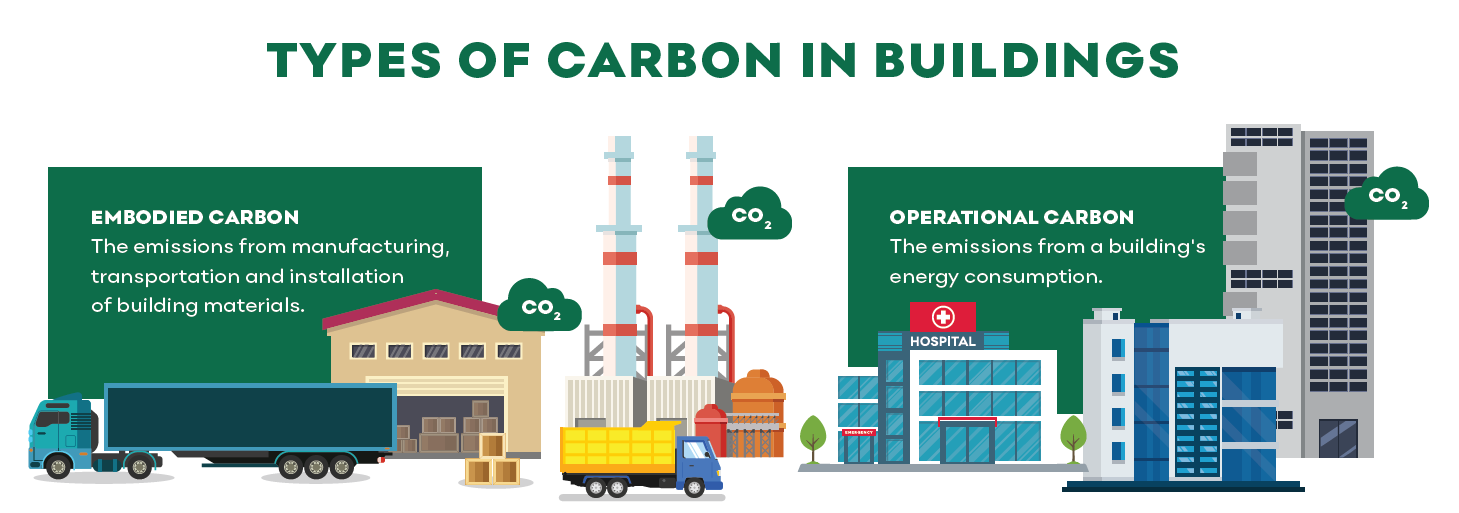

In a paper released earlier this year, ASHRAE announced its position that the global built environment must halve its 2015 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030, including cutting the embodied carbon of new construction at least 40 percent by 2030. ASHRAE defines embodied carbon as “GHG emissions associated with building construction, including extracting, manufacturing, transporting and installing building materials, as well as emissions generated from maintenance, repair, replacement, refurbishment, and end-of-life activities. Embodied emissions also include refrigerant releases across the building life cycle.”

Meanwhile in recent months, members of the International Code Council (ICC) Standards Development Committee have sifted through roughly 300 proposals for the next version of the Commercial Energy Code. Multiple submissions have included proposals to include (for the first time) embodied carbon provisions.

“This is really new territory for us. We are listening to experts and trying to get a grasp on this topic,” said Donald Mock, Plan Review Chief for Howard County’s Department of Inspections, Licenses and Permits and a member of the Standards Development Committee.

The committee is slated to release a draft of the new code for public comment in September. Several people familiar with the process suggest that any new embodied carbon provisions will likely be modest.

“The big change is that embodied carbon is a now a mainstream concept where it wasn’t just a few years ago,” said Wes Sullens, LEED Director at the U.S. Green Building Council and an expert in the carbon impact of construction materials, products and processes. “But you can’t suddenly add something super hard to the code. It has to be incremental change. Maybe you start with a 10 percent reduction or target certain materials.”

“Being a code official, I look at this from the point of view of whether it is enforceable and reasonable,” Mock said. “It doesn’t do any good putting something in a code that you can’t enforce. Also, this is a minimum energy code for buildings. You don’t want to turn it into a stretch code because if you do that, fewer jurisdictions might adopt it and you won’t accomplish anything.”

Noting that embodied carbon is “a whole new field” for many designers, developers, builders and product manufacturers, any new requirements would have to help the industry understand and adjust to this new approach to construction, and access necessary information and products, Sullens said.

For example, Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), which assess a construction product’s environmental impact over its lifespan, can help identify opportunities to lower a building’s embodied carbon. Although LEED began recognizing EPDs about a decade ago, such analyses are not yet pervasive in the construction products industry. Governments, industry leaders and individual companies, however, could drive the broader development of EPDs through code requirements or purchasing decisions, such as the federal government’s decision to use more low-carbon concrete and the commitment by many corporations to use more sustainable construction materials and finishes in their properties.

“It sends a clear signal to manufacturers when they hear requests over and over again for environmental information about their products from many different stakeholders. It becomes something they have to pay attention to and it can have a market transforming effect,” Sullens said.

“We have the technology to make reductions in embodied carbon,” said Andrew Klein, a code consultant for the Building Owners and Managers Association International (BOMA).

Responding to market demand, manufacturers of flooring and other building finishes have developed and documented more sustainable products. Low-carbon concrete has become increasingly available and represents a significant opportunity to lower the environmental impact of buildings such as large warehouses, Sullens said.

Members of the commercial real estate industry, however, caution that reducing embodied carbon will take considerable time.

“One of the things we always say in BOMA is give us time,” Klein said. “We are happy to move along with environmental efforts. But our members have to work within their budgets and stay accountable to banks and investors. We advocate for allowing five to 10 years to get to the next phase of decarbonizing rather than implementing rapid, mandatory requirements.”

Decarbonizing efforts, he added, should be broadened to cover things other than construction materials.

“Renewable fuels are not being put in codes yet,” Klein said. “With the push to go electric only, I would like to see exceptions for renewable propane.”

Regulators, he added, also need to realize that building owners “have already gotten to all the low-hanging fruit when it comes to decarbonizing. There is really nothing else that is cost-effective at this point so the burden should be more on the generators and distributors of energy.”