Adaptive reuse brings new vision, new life to struggling areas

For one happy, furry, carb-filled day last August, the building that has driven and symbolized the economy of Canton for more than a century went to the dogs.

Once the site of the largest can manufacturer in the U.S., the American Can Company was an industrial powerhouse in Canton from 1890 until it closed in the 1980s. Empty and derelict for a decade, the site found new life in an adaptive reuse development and channeled that new life back into Canton. Developers began transforming industrial properties along the waterfront into residential, office and retail/hospitality spaces. Inland, old buildings were rehabbed into hip offices and homes.

On that tail-wagging August morning, The Can Company’s owner, MCB Real Estate, celebrated the arrival of new tenants. Research showed that the once-industrial, once-struggling community was now filled with professionals, young families, comfortable retirees and dog lovers, said Brett Foebler, MCB Marketing Director. So to celebrate the opening of The Original Pancake House and the imminent opening of You’ll Never Walk Alone Veterinary Hospital, The Can Company hosted a “Pups and Pancakes” event, complete with free nail trims and silver dollar pancakes for every dog.

Developers, architects and city planners have long touted the power of adaptive reuse to change communities and strengthen economies. A project that transforms an abandoned factory into modern office, residential or retail space impacts more than one building. It attracts new workers, residents, shoppers and diners; spurs developers to launch other nearby projects; helps lower crime by activating spaces; and benefits the environment through brownfield cleanups and improvements to building efficiency and resiliency.

Baltimore has a wealth of potential project sites, and “we have birthed a development community here in Baltimore that’s capable of pulling off those transformations,” said Owen Rouse, Vice President of Investment Sales at MacKenzie Commercial Real Estate Services, LLC.

The impacts of those projects are myriad and spreading throughout the city.

The Can Company and Tide Point were two of the earliest projects that created modern “funky industrial workspaces” in Baltimore, said Scott Vieth, Principal with Design Collective, the architecture firm for both projects.

In addition to surrounding workers with high ceilings, huge industrial windows, exposed brick, restored wood and towering bell-capped columns, the projects gave workers and community members access to interesting and previously restricted sites.

“Tide Point had this amazing waterfront amenity where employees of the original Proctor and Gamble factory could go outside and eat lunch right on the water in the Inner Harbor. But the public was not permitted to go there,” Vieth said.

The redevelopment enhanced that stretch of waterfront with a large promenade and dock and opened the area up to the public.

The transformation of industrial buildings to office space also provides employers with a competitive advantage.

“Sometimes when you show a traditional office building to founders of startup firms, especially in the tech arena, they will say, ‘I don’t want to work in my dad’s office… I want a more fun environment – more creative, less stuffy,’” said Peter Jackson, Vice President of JLL. “Often the layout of old industrial buildings, like Brown’s Wharf or some of the mills along the Jones Falls, are more conducive to the buildouts that technology firms or creative firms want. In those large floorplates, you can create a lot of open space, collaborative huddle spaces and achieve a lot of density.”

That layout enables employers to optimize their operations and, combined with a cool location, attract and retain talent.

Within Baltimore’s central business district, adaptive reuse projects have been easing a market challenge and creating opportunities for community growth.

The migration of offices to new facilities in Harbor East, former industrial sites and other locations left a glut of Class B office space north of Lombard Street. In a little over a decade, however, developers have transformed about 3 million square feet of office space into apartments, condominiums and hotels. The projects range from the transformation of the stately former Baltimore Stock Exchange building on East Redwood Street to the $50 million mixed-use redevelopment of the Brutalist building at 2 Hopkins Plaza to the dramatic conversion of 225 N. Calvert Street into a multi-colored tower of apartments, lofts and hotel space.

That trend has been a “saving grace” for the office market. It has also sparked “a big transformation downtown. Now the lights stay on past 5 p.m.,” Jackson said.

That growing residential base has increased demand for additional retail, restaurants and amenities. It is also encouraging more employers to move back into the heart of Baltimore to increase their chances of hiring city residents who want to live, work and play in close proximity.

Following the success of redevelopments in Canton, Fells Point, Tide Point and elsewhere, developers are pursuing adaptive reuse projects in different parts of the city.

“They are putting together the capital stack of new market tax credits and historic tax credits to help bring vacant industrial sites, like the Hoen Lithograph building, to life in neighborhoods that have traditionally struggled to attract investment,” Jackson said.

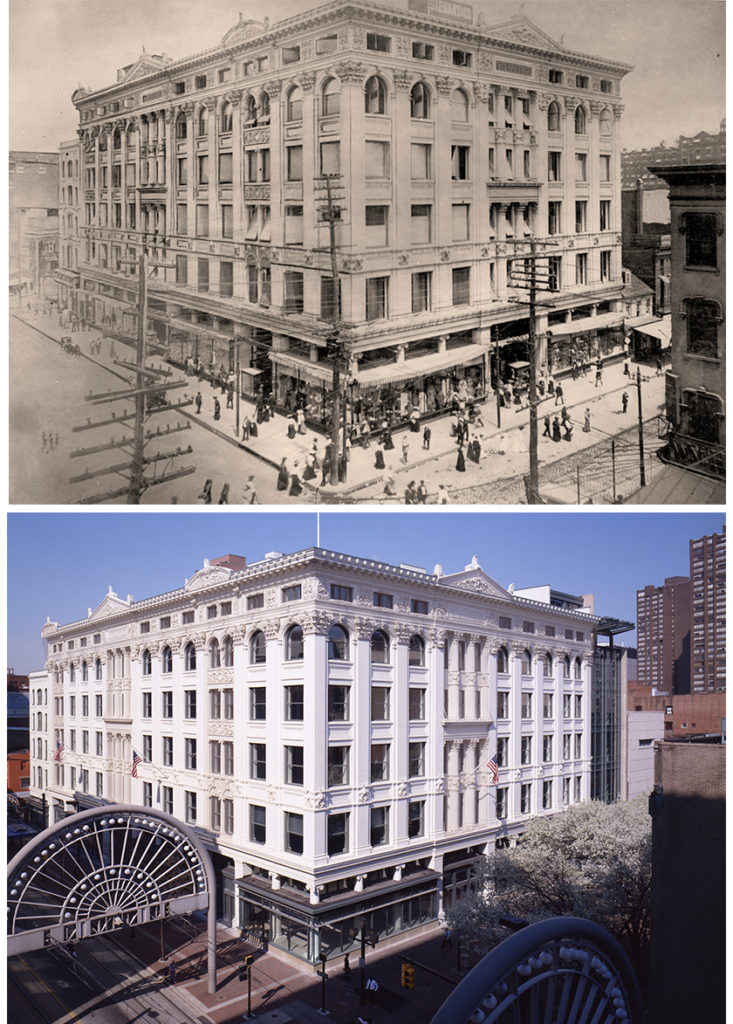

On the west side of downtown, Design Collective transformed the Stewarts Building into office space, saving a historic architectural gem and attracting new workforce to a struggling area.

“It was one of the grand old department stores along Howard Street. My grand-mother used to tell me how she would take the bus downtown and go shop there,” Vieth said.

“There’s more to be accomplished,” said Rouse, who expects developers to turn to other neglected neighborhoods.

“I wouldn’t call Central Avenue a Parisian boulevard, but it is a big road. And if you are looking south on Central Avenue, you are looking right down to the billion-dollar corner of the Exelon tower and Harbor Point,” he said. “At some point, people are going to realize that Central Avenue could be really impressive.”

Originally published in March/April 2020 NAIOP-MD InSites.