Challenging brownfield projects deliver enormous benefits

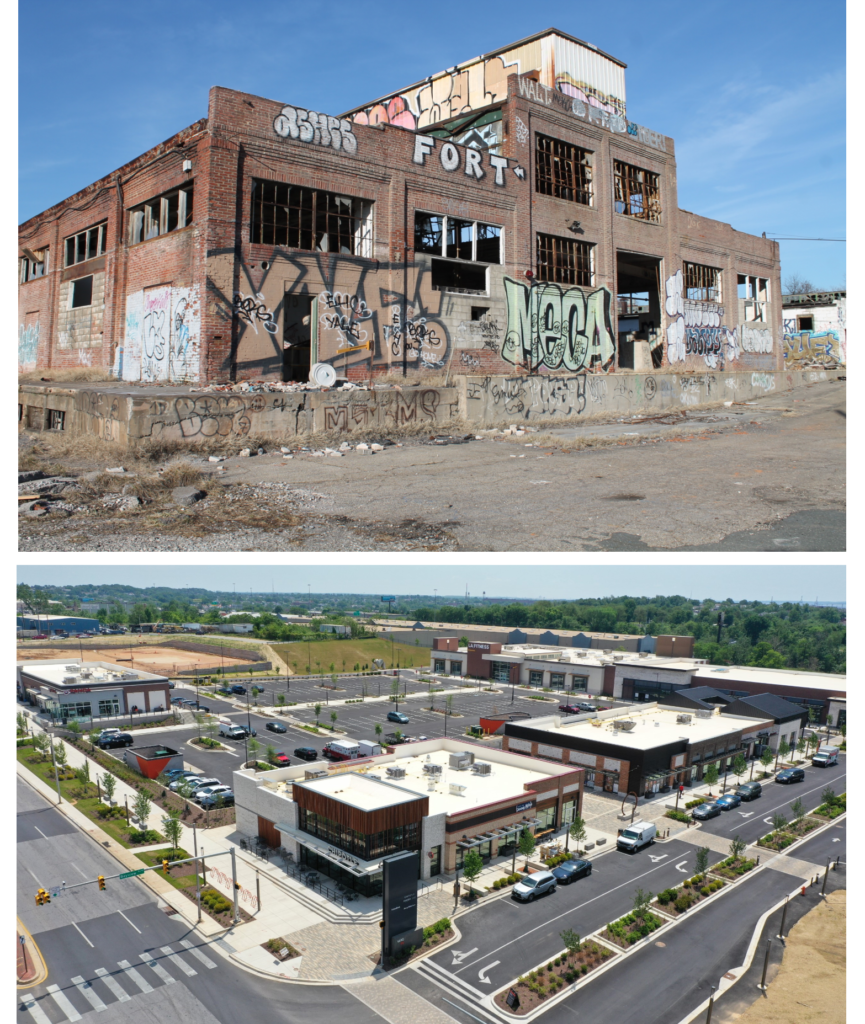

It was a picture-perfect example of industrial blight. Abandoned decades earlier, the hulking factory buildings, industrial furnaces and smokestacks were rusting, rotting and crumbling. Heaps of fallen brick, broken glass and torn-up concrete littered the sprawling, 20-acre site. Wanderers, mischief makers and vandals had tagged buildings, broken windows and doors, and repeatedly set fires. Meanwhile beneath the surface, buried industrial waste, leached chemicals and industrial equipment created environmental hazards beside residential neighborhoods.

Yet for years, David Bramble coveted the property.

A Baltimore native who once delivered newspapers near what was then a bustling porcelain and enamel factory called Pemco International, saw the brownfield as an opportunity.

“This is high-quality real estate. It was just encumbered by a really crappy building,” said Bramble, Managing Partner of MCB Real Estate. “It has direct exposure to I-95. It’s located between two awesome communities – Bayview and Greektown – and sits directly across from probably the most important institution in East Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Bayview Hospital. It has all the hallmarks of a site that needs to be redeveloped.”

In 2020, Bramble realized part of his vision as MCB completed Phase 1 of the Yard 56 mixed-use development on the Pemco site. Like any brownfield redevelopment, it took years of planning, meticulous (and sometimes unprecedented) environmental measures, collaboration and transparency with neighboring communities, extraordinary efforts to show investors and tenants the project’s potential, and careful construction on a sensitive site. But Bramble and other developers insist that brownfield redevelopments are one of the most potent tools in spurring economic growth and community improvements in areas that are blighted and struggling.

The environmental challenges of rehabilitating and redeveloping brownfields are both enormous and unique to each site.

Cleanup and site work at the former Pemco plant – which was contaminated with a range of volatile organic compounds and underground equipment – cost $1 million per acre, Bramble said.

At a pair of former ExxonMobil sites that had housed an oil refinery and storage facilities for petroleum products since 1865, 28 Walker Development has been cleaning up one of the largest oil-contaminated areas of Maryland in order to develop Canton Crossing and the Collective at Canton.

In addition to extensive environmental remediation, the projects have required “an extremely complex purchase and sale agreement, which came with specific deed restrictions, environmental land use controls and a fairly lengthy process to review and improve the development plan,” said Scott Slosson, Chief Operating Officer. “But the Maryland Department of Environment (MDE) has been a great partner of ours in working to develop these sites… They have been very helpful in establishing remediation plans that make sense. I think Maryland is very lucky to have an expert group that is forward thinking and practical, and helps come up with solutions that work for everybody.”

Along Baltimore’s harbor front, Beatty Development Group has worked with both MDE and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to remediate the former site of Allied Signal’s chromite processing plant and develop Harbor Point. Rather than remove huge amounts of contaminated soil from 27 acres of waterfront land, developers and environmental experts devised a plan to essentially create a secure landfill by installing a three-foot wide, 70-foot deep, subsurface slurry wall around the contaminated area, topping that area with a multi-layered cap of soil and impermeable plastic, and establishing an ongoing process for monitoring and maintaining the environmental safety of the site. A complex of wells and a transfer station enable onsite staff to prevent ground water, and potentially contaminants, from seeping out.

“We are doing things that aren’t done anywhere else,” said Jonathan Flesher, Vice President of Development at Beatty.

In addition to its complexities and cost, environmental remediation adds years to brownfield redevelopments. Flesher, who has worked on the Harbor Point development since 2003, jokes that “we usually say that it’s going to take 10 years to build but that was 20 years ago and we’re still working on it.”

And there are other complications. Investors are inevitably leery of projects that entail unknown environmental requirements and costs. Nearby residents typically have deep concerns about the safety and success of tampering with a polluted site as well as concerns about how a major redevelopment nearby could impact traffic, noise and other quality of life issues. Design, engineering and construction teams need to master (and sometimes invent) processes for dealing with the unique site requirements. Harbor Point, for example, has challenged teams to build on top of a landfill, develop unique solutions to elevation requirements and develop ways of minimizing rainwater infiltration when performing site work. Finally, would-be tenants have to be convinced that their retail or other facility will thrive on a site that has been an industrial plant or blighted plot for more than a century.

“It’s all incredibly difficult,” Bramble said. “Pulling off a project like Yard 56 is a huge, monstrous coordination exercise. We spent years and millions of dollars convincing people that this was a real project and it would succeed. To do these developments, you have to be a dog with a bone and have incredible determination to get it done, especially since you won’t know whether you are going to make any money for a long, long time.”

Despite those challenges, brownfield developments are proving to be some of the highest-impact projects in Baltimore.

Mid-pandemic, Harbor Point delivered a new building, Wills Wharf, and a park in 2020, and is about to start a new phase of development with the T. Rowe Price waterfront campus and Point Park.

“Harbor Point includes 9.5 acres of open space so when it’s all done, it’s going to feel like a bunch of buildings in a park. It is going to feel different from anything anywhere else in the city,” Flesher said.

Slosson said Baltimore “would be a totally different city without brownfield redevelopments. Brownfields represent unique opportunities to do urban infill and create economic hubs and thriving destinations in communities where previously those sites were vacant, contaminated eyesores.”

He points to the transformation of Boston Street. Once lined with green fence and idle industrial land from the CSX crossing to Conklin Street, the area has become a thriving retail district, a job source, an amenity to city residents and a draw to shoppers from the county.

“Our projects are also helping to drive growth beyond our sites,” such as apartment developments in Canton and Brewer’s Hill, he said.

Projects like Yard 56 are proving “hugely important because Baltimore traditionally has only seen major investments along the waterfront and improvements to the best neighborhoods,” Bramble said. “But every once in a while, we get to make a major investment in a neighborhood and get involved in needle-moving projects like this one that really contributes to the overall success of the City of Baltimore.”